To Mallorca via Switzerland and the French Savoy and Haute-Alpes

Time is a precious commodity. Everybody enjoys his limited days off work. Transport to the destination has to be as quick as possible. Since it is boring to stay too long in the same place vacationers increasingly prefer short trips, frequently to far away places. Their choice of transport is the plane. It is fast and no time is lost.

I propose a different approach. The route to the destination is considered to be part of the fun. It requires spontaneity in the choice of routes, trains and intermediate stops. On the way you will have to discover new places. You won’t stay too long in each because you will continue the next morning. Boredom will not arise easily. But you can always come back.

I use an interrail ticket and try to avoid high speed trains. First of all, those trains are too fast to really enjoy the scenery. Second in many towns for example in France and Spain they do not stop in the town center but somewhere in the middle of nowhere. The architecture of these modern stations frequently is disappointing. If you have to change trains you have no chance to see the town if the station where you have to wait is far outside. Moreover, in Italy, France or Spain high speed trains need a reservation which might be difficult to obtain on short notice. If you have to plan a long time ahead the whole spontaneity of this type of traveling is lost.

Utrecht Central. The night train to Zürich arrives

I already break my self imposed rules on the first day: I have reserved a seat on the night train from Utrecht to Basel. The train leaves Utrecht at 21.01. For the sleeper part of the train they do not sell reservations separately. As owner of an interrail ticket you have to use the seated cars. For this part of the train reservations are not required but highly advisable since it is usually full between Utrecht and Frankfurt.

Nowadays most long distance trains have a separate compartment for families with little children. For the number of families on these trains never enough compartments are available. Therefore I propose compartments for adults only. No little kids. One screaming kid can keep a whole car awake for hours. The success they have with their screaming has increased significantly since the disappearance of the compartment coaches. Instead of a maximum of 6 passengers, in the modern coaches, they can now keep the entire carriage awake. They know this and use it to oppress their parents and the tormented fellow travelers.

Next to me an Indian couple feed themselves on junk food while watching a movie on their tablet. In the past, travelers used containers made of metal or plastic that held sandwiches, vegetables, etc. for years. Now the stuff is packed in throw away plastic. The crackling of the plastic packaging is another main annoyance for anybody trying to sleep, not only on a train. And of course somebody has to take care of the garbage.

Basel SBB, Ch.

Fortunately most of my fellow travelers are young women who are permanently attached to their telephones. In the old times people were reading a book or the newspaper, activities which not only were silent but required silence and concentration. The use of mobile equipment comes with the permanent ping of incoming messages or the pop-up of the idiotic sound underlying a tik-tok clip. But both cannot compete with the combined noise of baby and packaging.

The girl facing me scratches the fresh tattoo she probably has got in a stoned mood in Amsterdam. Fingers clasped like claws around a dark blue arm with three white stripes. Outside the Jacob’s butcher shop is brightly lit in the middle of the night. The darkness of the night hides the ugliness of all the random cheap, featureless construction which has turned the countryside along the line between the Dutch border and Koblenz and after Mainz around Frankfurt and along a big stretch of the Rhine valley into one of the ugliest in Europe.

How can you sleep in a train seat? It would be best to have your legs stretched out, but due to the small distance between the seats, your legs will then stick out into the aisle, where someone will soon stumble. You can also sleep bending down with your head on your folded arms on the small folding table, but it is actually too low for that. Or you can sleep sideways in various possible positions. However, the knees are usually not designed for such a posture because they cannot be bent sideways. Strangely enough, I can still find some sleep most of the time.

Platforms, Basel SBB

The train runs non-stop to Venlo, where is waits on a siding between the containers of cargo trains to change the engine. That takes time and the delay at the subsequent stations is already more than an hour. The conductor reassures that this will not get less, but rather more. The young women start a long and fruitless discussion about possible connections. Eventually most of my fellow travelers leave in Mannheim in the middle of the night. It is quiet and empty now. Plenty of space to sleep but I am not tired anymore. The night train is scheduled to arrive in Basel SBB at 6.20, too early for any activities. So it is a streak of luck that it is 90 minutes late. A connecting train is ready to leave for Luzern at 8.03. Just enough time to bay a coffee and go down to the platform.

A typical SBB locomotie in Basel SBB

A ride on a train allows to look into the soul of a country. A look into the faces of the fellow traveler, the state of the infrastructure and buildings, the degree the countryside passing by has been raped by quick investment, the timeliness and accuracy of operations. In this respect the short move from Basel Badischer Bahnhof, the station of Basel in Germany to Basel SBB, the one in Switzerland, is like moving from the third world into the center of civilisaton. Abandoned, overgrown rails, decayed buildings, delays, destitution and moody faces change into affluence, tidiness, and a railway functioning like a Swiss watch. In consequence the Swiss railways intend to ban trains running from Germany into Switzerland because there unreliability and frequent delays also has influence on the Swiss punctuality.

The modern station of Luzern serves 1000 mm gauge in the foreground and standard gauge lines in the background

But the image is crumbling. The escalator to the platform in Basel is out of order. The door of the posh double deck train is not working and the bistro is closed. But the train moves smoothly through valleys and tunnels towards Luzern while a pretty girl is in love with her reflection on the screen of her phone. A dark, immigrant mother talks to her daughters in perfect Swiss German while they are mesmerized by the content of their telephones.

The station in Luzern which serves trains with two different gauges is a modern, depressingly ugly, dark concrete structure. Separated from it by a busy main road, the porticoes, the only remaining part of the old station, rests on the square in front. Girls hand out free flavored drinks to the passing passengers. It is handy to save some money here. To put your bag into one of the small automatic lockers for 6 hours sets you back 12 Franken, a cappuccino in town costs me 4.80 F, the cheapest take away Döner in the subterranean shopping mall under the station 14.50 F.

Not far from the station the wooden Kapelbrücke, the most famous sight of Luzern, allows to cross the river Reuss without the roaring noise of traffic on the neighboring modern bridge. On the other side the archways next to the river give shelter to a fish market. Most shops of the narrow streets of the historic old town house expensive brand stores, mostly devoid of customers. The shores of the lake are lined with graceful big old hotels where famous travelers might have stopped.

One of the grand old hotels along the shore of Vierwaldstättersee

But I pause here for another reason. Luzern is the home of the Verkehrshaus, the Swiss museum of transport. After I have bought my ticket for 30 F I have access to an enormous collection of cars, planes, boats, and, above all, trains. The history of transport also reflects many aspects of the history of a country.

The improvement in transportation conditions brought about by the railroad in these mountains has led to the construction of a tight network of railways which led into almost every valley and, in particular after arrival of the first tourists, to the top of many summits. The difficult mountainous terrain in Switzerland with tight curves and steep grades has led to spectacular architecture and many special innovations in railway technology. The museum collection shows milestones in Swiss railway development.

Steam locomotive Ec 2/5 No 28 Genf, built in 1858 for the Swiss Central Railway, is the oldest original locomotive in Switzerland. It was built for the Hauenstein line, which linked Basel to the Jura, the third mountain railway on the European continent. In 1850 a report by Stephenson and Swinburne recommended the use of cables to overcome the steep gradient. However, the construction of the Semmering Railway in Austria showed that modern mountain locomotives were able to overcome gradients of 1 in 40. The consequence was this design by Wilhelm Engerth where the rear half of the locomotive is supported by the bogie under the tender, while the coupled wheels are fixed rigidly in the frames. This makes a larger boiler possible.

Probably the most famous mountain line in Switzerland is the Gotthard Railway. Steam locomotive E 2/2 No 11 was built in 1881 for its construction. It uses the Brown system of lever-drive with elevated cylinders. The British engineer Charles Brown was the major founder of the Swiss Locomotive & Machine Works (SLM), the company which would become the major developer and producer of Swiss railway engines. This type of loco was particularly suited for construction and factory locomotives and steam tramways since the width of the locomotive immediately above rail level was reduced.

The many tunnels on those mountain lines had to be inspected regularly. In the time when electricity to provide sufficient light was a novelty, sufficient illumination in the tunnels was a problem. Special tunnel lighting vehicles like OKT No 3391 of the St. Gotthard Railway built in 1884 had to be developed. A steam engine inside the carriage drove a generator to supply electricity for two arc lamps and four filament bulbs.

Early tramways also used steam engines. Tram locomotive G 3/3 No 18 built in 1894 for the Bern Tramway Company was used there until 1902. Tramways were for the wealthy, but not very popular when driven by steam engines because of the smoke.

The railway between Liestal and Waldenburg was constructed in the middle of the 1880 economic crisis. To save costs, narrow curves and a gauge of 750 mm was used, the narrowest in Switzerland. In 1912, the SLM delivered locomotive No. 6. In 1958 it became the first railway vehicle to enter the museum.

Swiss technology was groundbreaking for mountain railways. To master steep grades racks are used. There are 4 different rack systems, Riggenbach, Abt, Strub and Locher, all invented in Switzerland. A display shows the differences.

The ladder rack, the first rack system was invented in 1871 by mountain-railway pioneer Niklaus Riggenbach. It was patented in France in 1863 and in the USA in 1865. In Switzerland it was first deployed on the Vitznau-Rigi Railway. It consists of two vertical U profiles between which trapezoidal bars were riveted at regular intervals.

In 1871 Riggenbach designed steam locomotive H 1/2 No. 1 “Gnom” for the quarry in Ostermundigen. It is one of the first examples of an engine with a Riggenbach rack drive. In rather flat terrain it used adhesive drive, on steep grades rack-and-pinion drive. From 1907 to 1942 it was used as shunting engine in the Von Roll steel works. Their general manager Dr. Ernst Dübi arranged for the preservation of the engine.

A later example of a rack steam locomotive according the Riggenbach System is HG 3/3 No 1063. It was built for the Brünig line between Luzern and Interlaken in 1909. The line is built in metre gauge and operates on the rack only to overcome the steep sections while the flat parts simply use adhesion. In 1941 the line was electrified.

No. 1063 is cut open to show the principle how a steam engine works. A volunteer operates the engine to show how the different cylinders work on the rack and the adhesion drive. It turns out that he is a retired pilot who had worked for many years in China to instruct Chinese pilots. Corona ended that career and turned him into a specialist for steam engines.

While the Brünig Bahn was steam operated for a long time, the connected Stansstad – Engelberg Bahn was electrified from the beginning. At the time, with a length of 22.5 km, it was the longest electric railway line. It used the uncommon three phase alternating current. Electric rack locomotive HGe 2/2 no 1 built in 1898 was the first electric locomotive with combined traction, using adhesion and Riggenbach type rack. It was used until 1964, when the line was rebuilt to standard current.

In 1882 Carl Roman Abt invented the lamella rack whereby two or three racks mounted side-by-side with the teeth offset. After the system was first deployed on the Harz Railway in Germany in 1885 it took until 1890 to be first used in Switzerland. The toothed rack was cheaper and allowed trains to travel faster and smoother.

One example is rack-and-pinion steam locomotive H 2/3 No. 3 built for the Brienz Rothorn Bahn in 1892 with improvements in 1935 and 1990. The line has 250 per mille gradients and the original steam engines are still used. They even have built some additional new ones recently.

In 1885 Eduard Locher invented a double rack system where two horizontal pinion wheels grip each side of the rack. With a guide disk on the underside of the wheels they are prevented from jumping out of the toothed rack. This system has ever been used only on one railway. The extremely steep Pilatus Railway opened in 1889.

The museum displays rack steam railcar Bhm No 9, which was in regular operation until 1937. The use of a railcar made it possible to save weight and therefore coal. The boiler was fitted sideways to the running direction to avoid dangerous variations of the water level.

In 1896 Emil Victor Strub designed a machined rack with involute toothing of a flat-bottomed rail and involute teeth machined into its conical head. It minimized the sliding and wear. It was first deployed on the Jungfrau Railway that same year. The construction lasted from 1896 to 1912. The railway leads into perpetual ice. With an altitude of 3454 m it still has the highest station in Europe.

The museum displays electric rack locomotive He 2/2 no 1 of 1898 supporting the carriage in a 4 axle unit to save weight. To protect against freezing, the locomotive and the carriage were lined with wood. Inside, felt cushions and plush created a cozy atmosphere.

The experiences with electrification on the steep grades of the rack lines finally led to electrification of the main lines crossing the alps. The line across the Lötschberg was built in 1913 and electrified right from the beginning. For Oerlikon Engineering Works MFO and BBC building the first series of a main line electric locomotive, Be5/7 No 151 for the Berne-Lötschberg-Simplon Railway BLS in 1913 was a great success. With their new single-phase alternate current system this engines were the most powerful electric locomotives in Europe at the time. However, the transmission of the huge power by connecting rods caused the rods to break.

While the BLS already used electric locomotives the newly formed federal state railway SBB CFF put the largest steam locomotives ever built in Switzerland into service on the Gotthard line in 1913. 30 of these locomotives were built by SLM, but already in 1916 it was decided to electrify the route. Locomotive C 5/6 No 2965 Elephant built in 1916 used steam superheated to 350°C and compound design with the steam being used twice, first in the twin high-pressure and then in the low-pressure cylinders.

To demonstrate the struggle of a fireman who has to constantly shovel coal into a hungry boiler to keep one of those elephants creeping up a grade, the museum has installed a demonstration box where visitors can shovel 100 kg of coal from left to right. Most stop after a few shovels. …. The need of electrification becomes obvious.

In 1919, the St. Gotthard route was the first major line of the Swiss Federal Railways CFF to be electrified. For the line, Oerlikon Enginering Works MFO built a completely new heavy freight locomotive, the famous crocodile. Be 6/8 II No 13254 built in 1920 consists of three sections. The brilliant idea behind the Crocodile was to mount the transformer, which is the heaviest component of the electric equipment, on a girder underframe, which is in turn supported by the two articulated under-chassis. This construction is extremely flexible in curves. The low, nose-shaped ends provide a good view for the driver, while the symmetry and the open drives gave the locomotive an outstandingly functional aesthetic appearance. The design was copied all over the world, and SLM was able to export similar engines to countries as remote as India.

The third Swiss railway to cross the Alps, the Rhaetian Railway RhB was built in meter gauge, and with gradients that were even steeper than those of the Gotthard Railway. In 1913 also the RhB started to electrify its new Engadine line using single-phase alternating current. BBC manufactured eight locomotives powered by a single, large motor. Electric locomotive Ge 2/4 no 207 stayed in service for 60 years without major modifications even though it had bad efficiency and high maintenance costs.

To better cope with the gradients and sharp curves the RhB ordered an electrical freight locomotive designed after their big crocodile sisters. Ge 6/6 I No 402 was one of 15 powerful locomotives built between 1921 and 1929.

In 1955 the BLS set another milestone by building the first electric locomotive with no unpowered axles and over 1000 hp per axle. Electric locomotive Ae 4/4 No 258 was able to haul bigger loads at higher speed.

The latest developments is to replace gradients of a line across a pass by tunnels. Simplon, Lötschberg and the new Gotthard tunnel are the pride of Swiss rail infrastructure projects. A big model demonstrates the engineering feat of building such a tunnel. The reality is in the news: after a derailment the tunnel is closed for month at the moment.

And, maybe involuntarily, the museum also demonstrates that railways have lost the attraction of the general public. While only a few people watch the brilliant demonstration of how a steam engine works, there is a long queue outside of people willing to do a test ride on a real truck. The railway section of the museum is congested and chaotic. The display of the history of a great and in the mountains only possible means of transport is in danger of becoming an infantile playground. But of course, it is much cheaper to let a truck ride around on the grounds than maintain an operating steam locomotive to let it steam up and down in the museum yard.

When I step outside it has started to rain. Using every means of protection I hurry back to the station to see how much Swiss trains have changed since those times displayed in the museum. From Luzern there are two equally attractive alternative routes for the continuation of my way south: the partially rack, narrow gauge Brünig railway via Interlaken or the secondary standard gauge line via Wolhusen, Entlebuch, Langnau and Konolfingen to my destination for the day Thun.

I have traveled on the Brünig line before and decide to take the line via Entlebuch. The line crosses the UNESCO biosphere reserve Entlebuch. It is an agricultural landscape thinly populated with little villages. Extensive moors border a dry karst landscape, floodplains, forests and meadows. More than 50% of the entire area is protected. However, the mountains are shrouded in clouds and it rains incessantly. The train ride is swift. Even the Swiss branch lines offer frequent services in comfortable and fast trains. There is no negligence for public transport in rural areas. I change trains in the modern station of Konolfingen and after only 2 hours I reach Thun.

The beautiful old town of Thun occupies an island in the Aare at the outlet of the lake of the same name and the slope of the Schlossberg above the river. Narrow and partially covered stairways lead up to the castle and the towns main church on the top. The rain has moved away and the town is basked in bright sunlight. The plateau at the foot of the church offers a clear view of the ice and snow covered tops of Eiger, Jungfrau and Mönch at the horizon behind the lake.

It is Sunday and they have their annual city run. Different courses are marked out and all generations are on the move across town. The advantage is that most of the motorized traffic is banned for the day.

The historic shopping street, Obere Hauptgasse, has elevated walkways above the road. But for me the main attraction is the maelstrom of the Aare shooting down from the lake. The heavy rains have caused the waters to swell and historic looking wooden weirs seem at the limit of their capability to tame the water. The view from the bridges into the azure – blue turmoil underneath makes me dizzy.

The shopping platforms above the main street in Thun

Without great expectations I have booked a room in a hotel called “Spedition”, mainly because it is the closest to the station and as always my backpack is far too heavy. The hotel got his name from the building, which used to be a warehouse. I could not have found a better place in Thun. The room is tastefully decorated and food and service in the restaurant are excellent. Town and hotel are one of those accidental internet discoveries which you bookmark in your mind as destination to return to.

Hotel Spedition

The next day I take the train from Thun to Zweisimmen. My idea is to take the Montreux Oberland Railway to cross from lake Thun to Lake Leman. The time for changeover in Zweisimmen is only three minutes. When the conductor comes to check my ticket I ask if this might pose a problem. She is surprised over the question but understands when she realizes that I come from Germany.

On the way to Zweisimmen

In contrast to the standard gauge BLS line to Zweisimmen the Montreux-Oberland-Bahn is built in 1000 mm narrow gauge. The connecting train waits at the same platform. It is a modern electric multiple unit that departs swiftly after everybody has boarded. Panoramic windows allow a sweeping view of the surround peaks – if those surroundings would not be covered in rain clouds and mist. There are tables between the seats and sockets to charge the appliances of those who are not interested in the countryside. There is no Wifi on the train but it is fascinating how well the internet network in these mountain valleys works.

Changing trains in Zweisimmen. The standard gauge train just arrived to the left

Between 1901 and 1905 this line was built to main line standards. It also was one of the first which was electrified right from the beginning. Regardless the difficult terrain rack section were avoided. This results in grades of up 1 : 13.5 of 7.5%.

Horseshoe curve climb after leaving Montreux. The lower track is visible at the bottom

After Zweisimmen the line climbs steeply up to the Saanenmöser Pass, the highest point on the line at 1,270 m. To gain height a double horseshoe curve part of which is in a tunnel is used. But what is this: Suddenly the train comes to an abrupt stop. After a pause the light goes off and on again – a restart. The train continues but stops abruptly again. Another restart. After that it runs well.

After the pass the line eases down into the valley and in a wide turn around Gstaad. The railway greatly helped to develop this area to become one of the hippest resorts in the Alps. To accommodate the wealthy the railway provided through trains with dining and saloon coaches of the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits (CIWL). These coaches were later sold to the Raethian railway and are still in use. At least on the through train of today such luxury is gone. The well-to-do do not use the train but come by private jet which can land on Gstaad airport visible in the mist in the back of the valley as the train eases down the slopes. However, there still is a modern successor of those luxury trains, the Golden Pass Panoramic Express, which offers touristic excursions.

After Gstaad the train passes the language border and enters the French speaking canton of Vaud. At Montboron the connecting line of the Transports Publics Fribourgeois shares the village Hauptstrasse with the other traffic. My train has to climb up steeply, again with the help of another horseshoe curve to reach the tunnel under the Col de Jaman, the mountain range separating the eastern Saane valley from the Lac Leman. The valleys are narrow here but the most spectacular part of the line starts after Sendy-Sollard. The height difference between the lake and the mountain pass has to be mastered. Far below Lac Leman is constantly visible and the traveler asks himself how the train can ever get down there.

The historic train of the Blonay - Chamby railway in Chamby

As is frequently the case, the weather changes completely after passing one of the main mountain chains of the Alps. After another horseshoe curve inside a tunnel we pass the little station of Chamby. It is the departure point of a short historic line to Blonay. The museum close to the station houses a spectacular collection of meter gauge railway material from different European countries.

After three more horseshoe curves and excellent views into the gardens of some rich people owning the expensive homes with a panoramic view of Lac Leman we enter the narrow gauge part of Montreux station.

Waiting for the train to Vallorcine in Martigny

On the other side of the platform the 13.11 SBB intercity train is ready to depart. I board and it sets off. The scheduled arrival of the MOB train from Zweisimmen was 13.11. A connection which can only be secured in Switzerland. I take this Intercity for the short trip to Martigny.

In Martigny I have 25 minutes for the connection to another narrow gauge train, this time up to Vallorcine, across the border into France to Chamonix and further. There is a friendly cafe in the well-maintained station and I use the break to have a cappucino and cheesecake. Then the train to the border pulls in and I am lucky: it will run through all the way to the end of line in St. Gervais Le Fayet, the end of this narrow gauge line.

The train to Chamonix has arrived

The train to Chamonix departs from the narrow gauge part at the side of the station in Martigny. Begin of the 20th century both the Swiss and French started to built railways towards Chamonix. In France, the Paris to Lyon and the Mediterranean Railway Company (PLM) began operations from St-Gervais/Le Fayet to Chamonix in 1901. Construction continued towards the Swiss border. In 1908, after 6 years of construction the Swiss rail lines joined the French after the final stretch had been finished between Argentiere-Vallorcine-Le Chatelard-Frontier. The Swiss part of the line is 19 km, the French 36.5 km long.

The steep climb out of the Rhone valley

This line is remarkable in several aspects. Common trains are operated by two different companies, the French SNCF and the Transports de Martigny et Régions in Switzerland. While 850 DC is fed by an overhead catenary in Switzerland they use a third rail in France. In Switzerland rack system Strub is used with a maximum incline of 20% while adhesion with an incline of 9% is sufficient on the French part. Originally the line was closed in winter. Following the construction of avalanche protection galleries and suitable tracks, quays, and snow plows, the line began running throughout the winter in 1935.

The border station

I don’t have to describe the ride since there is an excellent report of this train journey in the Guardian (see link below). In Switzerland this train ride gets as close to a roller coaster as possible. It climbs out of the Rhone valley at Martigny with an incredible incline, precipice to one side, vertical rock face at the other. The views are as spectacular as the tunnels and bridges necessary to master the terrain.

Third rail electricity of the French part of the line

At the border the train has a break and the Swiss staff hands over to the French. Most of the travelers are tourists, many of them from overseas. Strangely enough they are either occupied with their phones or they sleep. Most get off in or around Chamonix. Bad weather and rain has again moved in, but on the other side the glaciers can be seen moving down into the valley from the invisible heights above.

The Mont Blanc glaciers drifting down to the valley near Chamonix

While the layout of the railway has not really changed in 100 years the parallel road has. The enormous bridges of an elevated motorway follows the valley for long stretches. St. Gervais is announced by the huge compound of a factory turned black by its product: the produce graphite and fiber composites. I am looking for a rail track to deliver and ship goods. There is none. They use the motorway.

Motorway building in France

The narrow gauge line ends at the big station of St. Gervais Le Fayet. From here the SNCF continues on standard gauge tracks west to Geneva and Grenoble. The proper town of St. Gervais les Bains is on a plateau above the valley. St. Gervais Le Fayet is also the terminus of the Mont Blanc Tramway which connects to the town and to the viewing point Nid d’aigle at 2374 m. It is the highest point a railway reaches in France and forth highest in Europe. The height difference of 1792 m is reached on 1000 mm narrow gauge tracks. The steep sections with gradients of up to 24% is mastered with a rack system type Strub. Originally steam engines needed 2 h 20 min to reach the top. In 1956 the line was electrified. The new electric units reach the top in an hour. 3 of the original 6 steam engines are preserved. One is displayed next to the starting terminus in Le Fayet.

Transfer from the narrow gauge to standard gauge SNCF in St. Gervais

At the moment the summit at Nid d’aigle is closed. The Tête Rousse glacier which ends right above the terminus is prone to the formation of pockets collecting melt water. In 1892 a devastating flood of such a melt water pocket had rushed down the flank of the mountain, completely destroyed the hamlet of Bionnay and flooded the bath house in the town of Saint-Gervais. More than 200 people lost their lives. At present water pockets are drained by drilling holes to avoid the danger.

To get an impression of the might of the glacial water rushing down I don’t have to the tramway. At the upper end of Le Fayet is the Park Thermal. It features an abandoned big hotel, modern thermal baths and a miniature railway. A hiking path leads further up to a gorge where the waters from the Bon Nannt rush down in an impressive cascade. They have built a bridge right above the cascade. Through the gaps in the grid of the walkway of the bridge you see the gushing water. The noise is deafening.

The thermal baths of St. Gervais

I have booked a room in the Hotel Terminus, a grand old hotel that definitely has seen better times. The restaurant is closed. In the bar on the ground floor they advertise their pinball and table soccer games. The comfortable fauteuils stay empty. But the window of my pleasant room overlooks the street which is used by the tramway just before the steep rack section starts. A traffic light stops any motorists when the train is about to pass. The workshop and sidings of the tramway are behind the hotel.

On my question the chap behind the bar recommends the restaurant across the street. When I pass by at half past 6 it is still closed. The girl asks whether I want to make a reservation. It opens at 7. When I come back I am glad that I have followed her advice. It is getting full very quickly and they have to turn away customers without reservation. They serve local specialties. When I ask about tête de veau the lovely waitress frankly tells me that she doesn’t eat it. I order foie gras and lamb. Only once a year. The food is excellent.

The weather has not improved the next morning when I take the modern train from Le Fayet bound for Geneva to La Roche sur Foron. There I have 5 minutes to change to a train for Annecy. The train quickly fills up on its way. The conductrice comes for checking the tickets. A black guy fashionable clad in blue shirt and white jeans hasn’t got one. He also doesn’t have 100 € for the fine or an ID. His partner and children have a ticket. The conductrice shrugs her shoulders and carries on.

Inside and outside of the station in St. Gervais Le Fayet

The train arrives in La Roche right on time to change into a SBB EMU to Annecy. Unfortunately the noisy teenagers next to me not only change as well but also sit down close to me. It is a ride of almost one and a half hours to Annecy and also this train arrives on time at 11.16 sharp.

Departure in St. Gervais and arrival in Annecy

The timetable of SNCF is not catering for passengers who want to hop from train to train. It is difficult to find good connections which do not require long waiting times. This would not be a problem in an attractive town like Annecy. The station is close to the old town which is always good for a pleasant walk. However, where do you leave your luggage? Very few French stations have lockers, a consequence of the past when lockers where used for placing bombs. But there is usually plenty of staff in any French station and they point at a cafe across the station square where I can leave my backpack. The friendly owner charges 3 € an hour. He also explains how I easily get into the old town.

It is still raining but fortunately Annecy is well prepared for that. Most of the alleys in the pedestrian streets of the old town have arcades where you can walk or linger protected from the elements. Also the shops have profit from that protection since they can showcase their products without getting wet.

The river Thiou separates the old town of Annecy in a number of islands. With its numerous bridges it is sometimes called the French Venice. Although this is a gross exaggeration the old town is usually full of tourists. It is a positive effect of the bad weather that most of them stay away today.

From Annexy I take the 12.43 train to Grenoble, another ride of about one and three quarter hours. More than 100 minutes that a screaming little kid manages to run up and down the aisle of the coach. The frustrated parents have given up. Next to me a couple with big backpacks. Hikers who have escaped from the rain into the train. Meticulously they clean their brand lunchboxes. I guess they are German and I am right…. At least they keep quiet.

Transfer rest in Grenoble

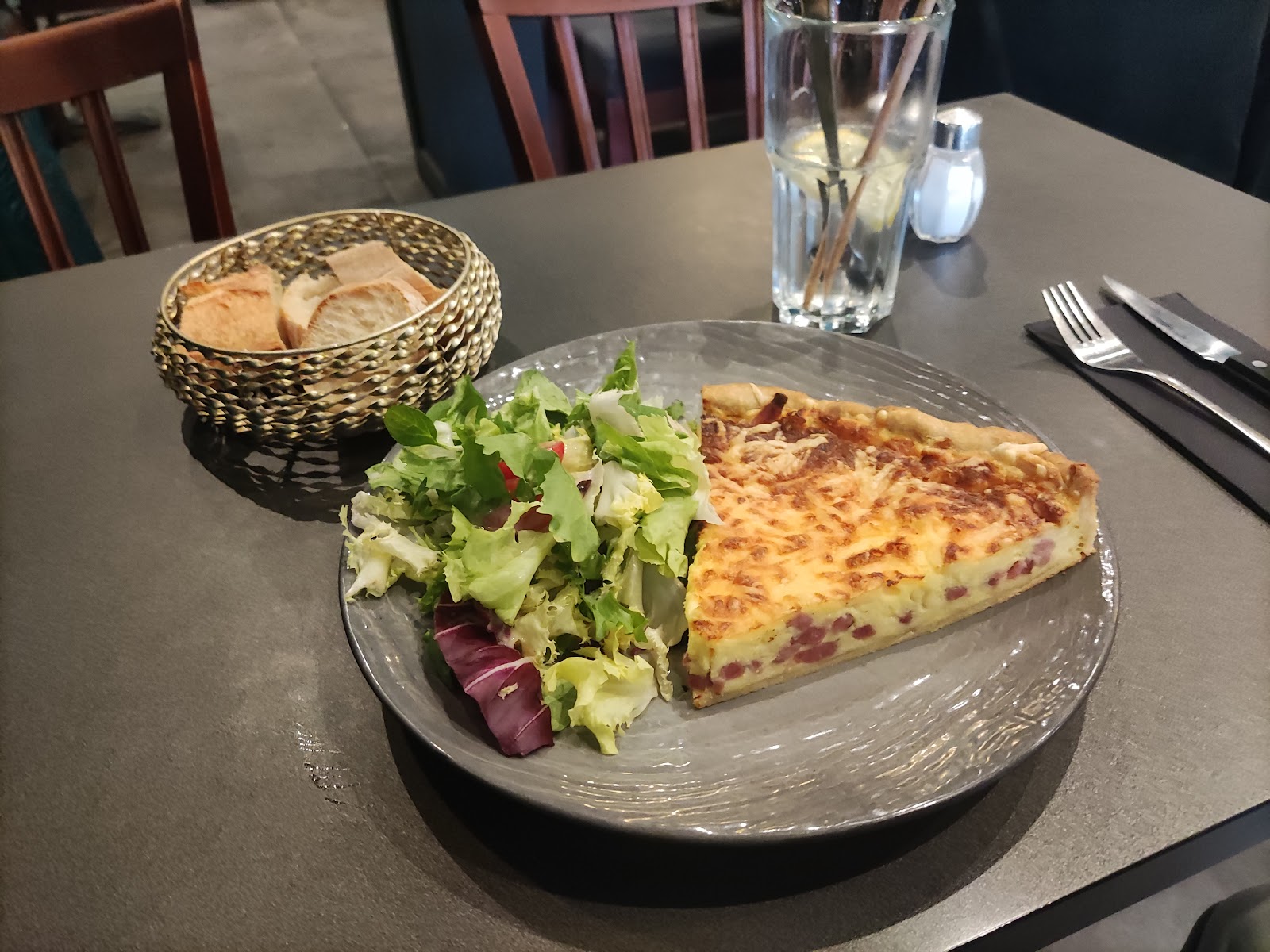

And in Grenoble, again, I have to wait for another one a half hours from 14.27 to 16.08 to get the connection to Gap. I cannot find a space close to the station to leave my luggage so I retire into a cafe at the station square to have lunch. For little money they serve an enormous piece of quiche. Outside the modern trams pull in and out of the square. On the television there is news that the constant rains have washed away road and railway between Chambery and the Italian border.

The cigar before departure to Gap

The line from Grenoble to Gap is part of the ligne des Alpes, the direct connection from Grenoble to Marseille. It has been classified in the SNCF "Loisirail" list of tourist lines because it offers magnificent panoramas of the Alps, the Gresse valley and the Trièves. Unfortunately, today everything is shrouded in rain.

Old guards cottage along the line to Gap

The single little railcar (nicknamed cigar in some countries) is quite packed when it leaves the station in Grenoble. Through rather flat country the single track line crosses the suburbs of Grenoble until it reaches Vif.

The huge abandoned station of Saint-Georges-de-Commiers

One stop before Vif, Saint-Georges-de-Commiers was the departure point of the Petit train de La Mure, an electrified 1000 mm narrow gauge railway which was built to connect a coal mines in the mountains to the main line. The transport of coal stopped in 1988 but the touristic value of the line was already recognized and tourist trains had started to run in 1978. Next to the grades it also features numerous viaducts and tunnels. Unfortunately, in 2010, a massive landslide disrupted the line and at present only the upper part is still used.

View from a viaduct into the mist

After crossing the La Rivoire bridge, behind Saint-Georges-de-Commiers, the line makes a detour via Vif station before climbing up the slope in a double horse shoe curve to overcome the significant difference in altitude. Part of it is in a S shaped tunnel. Grand Brion Tunnel above Vif with a length of 1175 m is the longest of the 12 tunnels of the line. The grade in combination with the "S" shaped tunnel was a nightmare for the staff of the heavy steam locomotives 242 AT, 141E and 141F of the PLM and later 141R of the SNCF used on the line who fought with the lack of oxygen and had to wear a mask.

The line also features nine masonry viaducts of more than 100 m, most of them in curves. The longest, the Darne Viaduct or Orbannes Viaduct is 250 meters long and 44 meters high. The 210 m ling Casseire Viaduct has a height of 47 meters. If Harry Potter would have known, he would have moved to France (Glenfinnan viaduct is 381 m long and 30 m high).

Most of the line passes through isolated empty regions. Old signal boxes, masonry overpasses and telegraph poles remain. Some are covered in graffiti. Who are those people thinking about carrying spray cans into this remote area just for that?

Outside the rain slashes against the windows of the railcar. At the occasional stops the few waiting passengers huddle together under their umbrellas. In each station a station master comes outside upon arrival of the train and it is his duty to wave it off. This is France. The unions have successfully prevented the closure of ticket counters, in some cases even if there was no train for years. In Digne, for example, where the SNCF line meets the narrow gauge line from Nice, both, SNCF as well as the Chemin de fer de Provence, maintain a ticket office although the SNCF line to Digne was closed many years ago and the narrow gauge line is temporarily out of service. But freight traffic has all but disappeared also here and the former loading bays are overgrown and the freight sheds in ruins.

Close to Veynes – Devoluy the line joins the main line from Valence to Briancon. Station and both lines look like nothing had been done in half a century.

After two and a half hours and 136 km the railcar arrives in Gap. Right across the street from the station is Hotel Le Michelet. It is in a big high-rise, but only occupies the lower floors. My room is on the ground floor. The friendly manager also runs the curious snack bar which doubles as the entrance for the hotel. You feel like you've been transported to the American fifties. Pastel colors, bays with red artificial leather benches, juke box and the notorious photo of Marilyn Monroe.

Hotel Michelet in Gap

Gap is the regional capital. Although it lacks spectacular sights it has a pleasant pedestrianized old town. To make it more attractive for the shoppers they have suspended colored ribbons and umbrellas above the street. Probably pleasant to have shade in summer. Next to the hotel is a magnificent park with the departmental museum and a bandstand.

The departmental museum in Gap

I have spent nearly 9 hours to ride from St. Gervais to Gap and get out to find a restaurant. But now, at around 7 pm, everything seems to be closed. Maybe because it is Monday evening? Finally I find a restaurant in the old part of town. On the way back to my hotel I notice that most just opened late.

Decorations in the streets of Gap

Notwithstanding the American decor the breakfast in the hotel is the conventional buffet. Then I take the train from Gap to Marseille St. Charles. Another well occupied railcar. This part of the ligne des Alpes is far less spectacular than the route north of Gap. But there are some interesting looking little towns and I note down Serres for a later visit. Meanwhile the weather has changed to the blue sky you can expect from the Mediterranean at the end of August. At Chateau Arnoux-St. Auban the abandoned line to Digne branches off. It is strange that they have closed the branch to Digne. Most of the trains from Marseille north end at Aix-en-Provence.

Sunshine in the morning in the station of Gap

The train to Marseille arrives from Briancon

We arrive in Marseille on time. The first thing I see is a group of foreigners herded together by police. The station of Marseille St. Charles is one of these typical French beauties built by the PLM (Paris-Lyon-Mediterrané) railway. The station building is high above the town and a long flight of stairs is a nightmare for those lovers of roller cases.

The staircase leading up to the station Marseille St. Charles

Typical PLM station hall and old port in Marseille

I take the next train to Toulon. Soon the blue of the Mediterranean sea shines on the right. We pass the station of La Ciotat. In 1907 pétanque was invented here. Braque, Friesz or Jongkind painted here. La Ciotat was also the setting of one of the first projected motion pictures, L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat filmed by the Lumière brothers in 1895. Today the land along the line all the way from Aix en Provence is spoiled. Ugly construction everywhere. What is left of the rural peace painted a hundred years ago by the impressionists? But the popularity of their paintings contributed to attract those later visitors who caused the building boom.

Although my train is on time there is chaos in the station of Toulon. There are no ongoing trains in the direction of Nice and the station is packed with waiting trains. Probably therefore there are no taxis available and I drag myself in the heat to the hotel I have reserved close to the ferry port. It is quite a challenge to find the hotel which they have hidden in the upper part of a shopping center. Drenched in sweat I dump my bag in my room.

Toulon is the most important French naval port in the Mediterranean and had been heavily fortified to deter foreign invaders. Unfortunately little is left of the fortifications. However, there is a pleasant, fully pedestrianized old town. In the warm afternoon sun the cafes are packed.

But as soon as the sun sets the narrow alleys of the old town are completely deserted. All the people seem to have magically disappeared. In an empty restaurant we meet two Austrian brothers waiting for a ferry to Corsica. They have bought property there and want to turn it into a sustainable vacation home. One has stayed in Uganda most of his life, the other has worked as a correspondent at the EU in Brussels. They are fascinated by stories writers wrote about the town a century ago.

In the streets of Toulon

Toulon being a big town and naval base was a popular stopover for artists and writers staying in the area. They came to get medical treatment, shop like Aldous Huxley, visit the brothels like Evelyn Waugh or opium dens like Cocteau. Joseph Conrad, Edith Wharton, Paul Bourget, Katherine Mansfield, D.H. Lawrence and Ford Madox also found inspiration and beauty in the area. The old town is full of galleries, many with photos exhibitions, and there is an arts district.

I walk the deserted streets to the hotel next to the harbor. The odd drunkard staggers through the alleys. A couple with a bicycle carrying shopping bags tinkling from bottles fall over. The bottles roll down the pavement. Dark figures hang around in corners and entrances. I am glad when I have regained the entrance of the hotel, which is hidden in a shopping center.

The ferry for Mallorca leaves at 6 in the morning. Eventually they send a message that it will be delayed by an hour because of the storm the days before. It is a long trip. At the end of the season the boat is next to empty. After October it does not run at all. After 15 hours we arrive in the dark and sleepy port of Alcudia.

The modern island railway in Mallorca: Inca station

In five days I have spent 1 day 6 h and 22 min on 15 different trains and 15 hours on a ferry.

Sources:

No comments:

Post a Comment