Train # 170 on the Northeast Corridor between New York and Boston

Massachusetts bay and what later became Boston was the area where the immigration of white settlers into North America started to a greater degree. The reasons were religious conflicts between the British king and the Anglican church of England and the Puritans, a Calvinist group who were strongly represented in the British Parliament. In 1629 the British King Charles I dissolved the Parliament. The situation became so uncomfortable for the Puritans that around 80.000 decided to emigrate to Ireland, the West Indies, New England and the Netherlands.

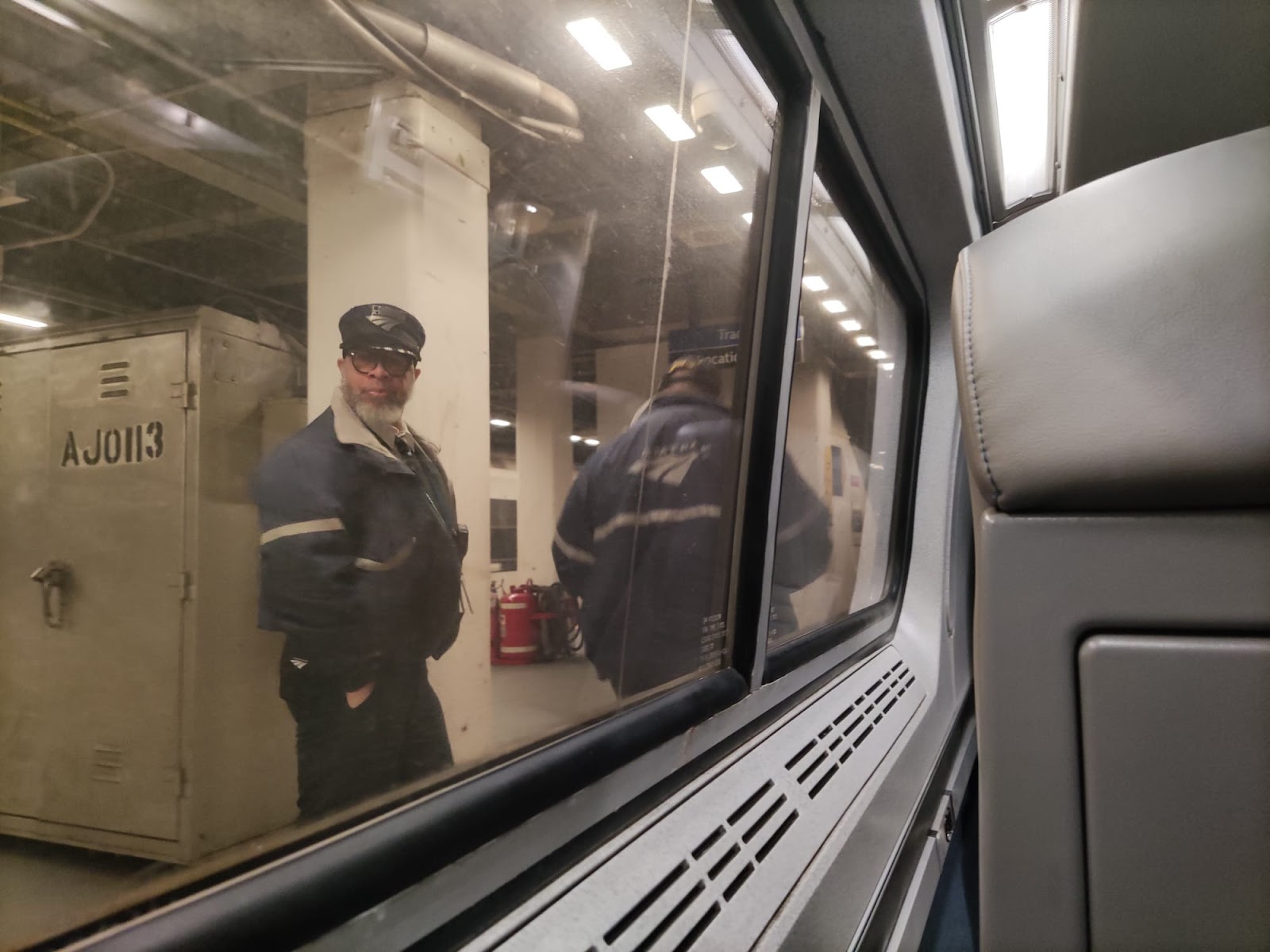

Penn Station in Manhattan

But the early arrival of settlers in 1630 is not the only reason for Boston’s importance in American history. Boston is the place where the movement for independence of the colonies started. It therefore became a symbol for what is regarded as the biggest asset of American culture: liberty and freedom.

When you want to travel from New York to Boston the journey starts at Penn station on 32nd street and 7th Avenue. That was not always like that. Manhattan is an island between Hudson and East river. Originally the railway between Washington, Philadelphia, New York and Boston ended at the Hudson River in New Jersey when you arrived from the South and at the East river in Stonington from the Northeast. A ferry had to be used to come to Manhattan. The Southern route was owned by the Pennsylvania Railroad, one of the grand railroad companies serving the eastern United States. The route towards Boston was owned by the New York, Providence & and Boston Railroad resp. the New York, New Haven & Hartford railroad.

Access from the west was easier since it did not require the crossing of wide estuaries. The line into Manhattan was owned by the New York Central railway. Since 1871 they had a station on Park Avenue and 42nd street. It was Pennsylvania RR greatest competitor for the route to the great lakes and Chicago. The Pennsylvania Railroad had a big disadvantage since they had no direct access to Manhattan.

Grand Central station

For the ferries between Manhattan and New Jersey the Pennsylvania Railroad built a new ferry terminal as late as 1897. But to meet with the competition by the New York Central already in 1901 Pennsy’s president Alexander Cassatt announced a plan to build a tunnel under the Hudson river to connect the line from Philadelphia and Washington to Manhattan. Two single track tunnels were built and opened on November 27th, 1910.

It also involved the construction of a huge representative station, Pennsylvania station, opening the same day. The Pennsylvania railroad compared its importance to the opening of the Panama canal. The station, designed by McKim, Mead, and White, was considered a masterpiece of the Beaux-Arts style. Upon its opening the New York Times reported:

“As the crowd passed through the doors into the vast concourse on every hand were heard exclamations of wonder for none had any idea of the architectural beauty of the new structure…. From end to end the station was ablaze with lights.”

A station of such brilliance of course was an open wound for the New York Central. The competitor answered by building a station able to compete with Penn station. Grand Central Terminal opened on the site of the previous terminals in 1913.

Access to the trains in Grand Central

Grand Central has 44 platforms, more than any other railroad station in the world. The platforms are all below ground on two separate levels; 30 tracks are on the upper level for intercity trains and 26 on the lower for local trains, of these, 43 tracks are in use for passenger service, while the others are used to store trains.

The original Beaux-Arts design for Grand Central's interior was designed by Reed and Stem, with some work by Whitney Warren. At the center of the main hall is an information booth topped with a four-sided brass clock, which became one of Grand Central's most recognizable icons.

Selfie taking in Grand Central's main concourse

With the construction of the tunnel these two stations had access to the south via the tunnel under the Hudson river operated by the Pennsylvania railroad and to the North along the Hudson river valley by the New York Central Railroad. Both routes also served competing express traffic towards the West, in particular the great lakes and Chicago. However, for the access to the east, i.e. Boston, it was still necessary to take a ferry.

Already in 1832 the New York, Providence and Boston Railroad was created to provide a rail connection between New York and the east. The line ended in Stonington, access to Manhattan was by ferry. Only in 1917 the Hell Gate bridge across the East River was built. This allowed uninterrupted rail traffic for 457 miles all the way from Washington via New York to Boston. The line which now is called the North-East Corridor was finally finished.

Hell's gate bridge

Since the southern access to Manhattan and the Penn station was in a tunnel the line was electrified from the beginning. After 1933 the entire route between New York and Washington was electrified. The electrification of the route via the Hell’s gate bridge took much longer. After 1914 electric trains could travel from Grand Central Station, which never saw a steam engine, to New Haven. The electrification all the way to Boston only was finished by 2000.

Old electricity mast on the way to New Haven

Since the southern part of the Northeast Corridor was electrified very early by the Pennsylvania Railroad, the eastern access to Manhattan by the New Haven Railroad and the line between New Haven and Boston by Amtrak, there are three different catenary systems. Between Washington, D.C., and Sunnyside Yard just east of New York Penn Station, 12 kV 25 Hz originally built by the Pennsylvania Railroad are used. From there to Mill River just east of New Haven station the former New Haven Railroad's system modified by Metro-North employed a supply of 12.5 kV at 60 Hz. From Mill River to Boston the modern 25 kV 60 Hz power supply built by Amtrak is used. Amtrak's electric locomotives can switch between these systems.

When rail traffic suffered from the one-sided investments in the construction of highways in the 1950’ies and 1960’ies both the Pennsylvania railroad and the New York Central began running into financial problems. Since the costs of maintaining the station were enormous the Pennsylvania railroad tore down a big part of Penn station in 1963. The rail infrastructure was moved to an underground station which is still used today. On the former station grounds they built the Madison Square Garden. The New York Times called the demolition of the original station as a "monumental act of vandalism". The demolition in fact catalyzed the modern preservation movement for historic architecture.

About the underground replacement of Penn station architectural historian Vincent Scully commented: “One entered the city like a god, one scuttles in now like a rat.”

The situation was improved slightly by the opening of Moynihan Train Hall, an expansion of Penn Station into the Farley Post Office building, in 2020 and an expansion of the Long Island Railroad concourse with a new direct entrance. Penn station also serves New Jersey transit and the airport trains to Newark depart from yet another part of the station.

When you finally have found the station – and Moynihan Train Hall where the Amtrak trains leave inside the station – you find a pleasant light space with elevators as access into the dark abyss where the platforms are supposed to be. As always I am much too early but there is a waiting area for ticketed passengers. After you have shown your ticket you find comfortable seats, chargers for your telephone and big photos displaying how luxurious this space once has been. There are also plenty of information screens and announcements when your train is ready to board. Like in many European countries the departure track is only announced and opened to the public 10-20 min before departure, i.e. when the train has arrived and descending passengers have disappeared. My train, Northeast Regional number # 170, scheduled to depart at 8.46 am, seems to be delayed.

Meanwhile everybody has recognized the importance of train traffic for New York. There are big plans for a new Pennsylvania station, which will probably cost the life of the Madison Square Garden, which shouldn’t have been built there in the first place. The concession for its operation was recently only extended by another 5 years to allow construction of the new station. This would be combined with the long overdue construction of additional tunnels under the Hudson river to enforce the present structures built more than 100 years ago. Signal or track failures frequently cause cancellations and delays since one of the now existing two tunnels has to be closed. For the traffic to Boston the extension to a four track tunnel has already been finished.

Special nostalgic New York Central train in Grand Central Station

In 1968 the next to bankrupt Pennsylvania Railroad and the New York Central Railroad merged to become the Penn Central. It was not a big success and already went bankrupt in 1970. The replacement became Amtrak. It was found in 1970 to rescue the remaining passenger rail traffic in the United States. In 1972 they counted 16.6 million passengers, in 1981 already 21 million. In 2024 Amtrak counted a number of 32.8 million passengers. More than 50% of Amtraks customers used the Northeast Corridor.

Historic luxury Pullman car

“It would be difficult to overstate the importance of the Northeast Corridor to both the regional and national economies.” Amtrak executive Vice president and chief to Northeast corridor (NEC) Stephen Gardner in 2015 “Millions of people depend on a reliable and functioning NEC and greater federal capital investment is vital to insure it stay that way.”

Lounge car on historic pullman train

Grand Central Terminal served intercity trains until 1991, when Amtrak began routing its trains through nearby Penn Station. Since that time the Terminal only serves regional railways like the Long Island Railroad. However, Grand Central Terminal serves some 67 million passengers a year. During morning rush hour, a train arrives at the terminal every 58 seconds.

In addition, Grand Central Terminal is one of the world's ten most-visited tourist attractions. Not counting the train passengers, there were around 21.6 million visitors in 2018 who mainly came there to take a selfie. This of course also is the fault of the proprietor. When you organize Christmas markets in a train station you shouldn’t be surprised if you have visitors who have never taken a train.

On 11.12.2000 Amtrak introduced the high-speed train Acela. It looks a bit like a French TGV but is built in the US. The condition of the tracks only allows high-speed service of 240 km/h on about 80 km of the entire distance of 729 km of the Northeast corridor. On the 368 km between Penn station and Boston South station the Acela is not much faster than other trains. Next to Acela the route to Boston is served by the Northeast Regional which takes around 4.5 h to Boston. These trains are pulled by the ACS-64 (Amtrak City Sprinter) locomotive built in 2016 by Siemens.

Train traffic seems to be a bit out of order today. This seems to affect in particular the Acela trains, which seem to either be seriously delayed or canceled. Northeastern regional 170 seems to be delayed at the entrance to the Hudson River tunnel but for the time being it is still running. Finally, with a delay of about 20 min, the departure is announced. Assisted by barrier tapes and the watchful eyes of a couple of employees a neat queue forms for boarding. Disabled and people with little kids are allowed to board first. The tickets are not checked upon boarding. Amtrak tickets are restricted to a certain train. The earlier they are booked the cheaper they are. Therefore changing trains will usually involve costs. I have paid 103 $ for the trip to Boston when I booked it a week in advance. After you have got a ticket it is first come, first serve on the Northeastern trains. So everybody in the line scuttles down and along the platform to get a good seat. Not that there is much difference. It is either left of right of the aisle, window or aisle and in direction of travel or with the back to it.

Train 170 is not very full. I get a window seat to the right side of travel, i.e. towards the coast. As soon as the train has taken off the conductor comes to check the tickets. Then he puts a piece of paper above your seat to indicate that the seat is occupied and the ticket checked.

The cars are not very modern, but, or better therefore, rather comfortable. There is a reading light, sockets, a table, a net for your belongings and plenty of space for luggage. Each car also seems to have at least one working toilet. Northeastern regionals usually have a bistro serving drinks and light meals and there always is a silent car. And the silent car indeed is silent. When I travel back to New York at night the light is actually turned off there to allow people to have a nap. Unfortunately there are no central arm rests and no hooks for coats.

The train passes a post-industrial landscape outside. Rusty steel structures, junk-yards, car-parks, even clusters of ship-wrecks in the mud. The last domains of nature are the golf courses. The first bits of nature appear only after the train has left New Haven.

We arrive in Boston almost on time. I depose my stuff in the hotel and have another couple of hours left to have a walk around town. Sightseeing in Boston is easy: there is the freedom trail, a red line in the pavement which connects all the sights related to the formation of the colony and the struggle for independence allover the town, but also a trail related to the history of African Americans in Boston. It links buildings in Beacon Hill, one of Boston’s poshest and nicest neighborhoods.

After the Puritans had settled in the new world and had overcome the initial difficulties, trade went well and for around a hundred years the colony developed and prospered. However, between 1756 and 1763 Britain participated in the 7 years war, a struggle which initially involved Prussia and Austria but eventually developed into a kind of world war with fighting also between the old arch enemies Britain and France. It drained the British treasury to such an extent that King George III, who ruled since 1760, thought about new ways of raising money. For the colonies in North America this resulted in the stamp act of 1765. The idea was to raise money through a tax on all legal and official papers and publications circulating in the colonies. Riots started immediately in the colonies. The stamp act was revoked in 1766.

Old Northern Avenue bridge

However, celebrations held on the occasion of the revocation were premature. Already in 1767 the townshend act was introduced. It involved taxes imposed on import of glass, lead, paint, paper, and tea into the colonies. The riots restarted and the colonies answered with an importation boycott. To maintain order the British sent troops in 1768.

The situation in Boston was tense and went out of hands on March 5th, 1770. A crowd threw snowballs and other items at British troops. Intimidated, the soldiers opened fire and five colonists were killed. Interesting enough one of them was a black man. The event is called the Boston Massacre and generally seen as the beginning of the American revolution.

Every detail about the American Revolution is meticulously studied and the remains painstakingly preserved. The victims of the massacre as well as many others involved in the revolutionary events are buried on the Granary Burying ground in the center of Boston.

This is not Boston’s oldest cemetery. Many of the Puritans of the 17th century are buried around the corner at the King’s chapel burying ground.

This cemetery is much older than the neighboring church which was built as Anglican church around 1749. Of course none of the obstinate settlers were willing to give land for an Anglican church. That had been what they were running from. Eventually the British Governor seized a corner of the existing graveyard to build the official church.

Old state house

Since 1713 the governor resided at the old State house. Built in 1713 this was were the British administration and the governor met. Since it also was the meeting place for the Massachusetts assembly, the representation of the settlers, it was the place where the initial confrontations took place.

Not far from the old state house is Faneuil hall built in 1742. In the basement it housed a market hall while there is a meeting room on the first floor. After a fire it was rebuilt in 1761. Its weathervane is a grasshopper. It might have been copied from the Royal exchange in London, of which Faneuil, the builder, was a member.

Historic Haymarket area

The colonists started to organize. In Boston the resistance centered around two men, Samuel Adams, the brain, and John Hancock, the financier. The main dispute arose from the fact that the Parliament in London decided on taxes in the colonies who were not represented in the parliament. In 1773 another tea act was introduced. Interesting enough this was not a tax but a subsidy. Since the East India Company had not sold enough tea to the colonies their warehouses in London were full and the company at the brink of bankruptcy. The parliament had introduced a subsidy of 1 shilling per pound. That way the company’s tea was cheaper than the tea smuggled into the colonies by other means.

Between November 28th and December 15th 1773 three ships of the East India company loaded with tea, the Dartmouth, Eleonor and Beaver, had arrived in Boston harbor. The law required the unloading and tax payment within 20 days of arrival. The locals refused to unload the tea. After deliberation in the meeting house a group disguised as Indians boarded the ships on December 16th and dumped the crates of tea into the harbor. The event will be known as the Boston tea party.

Old South meeting house where the Boston Tea party was planned

Punishment for the tea party followed suit. The British closed the port of Boston and abolished all institutions of self government of the colonists. Trade in Boston collapsed. Ruin of the rich traders was imminent. The colonists answered by training a militia, the minutemen. Stocks of weapons and ammunition were hidden in the countryside.

In April 1775 the British, who became aware of the resistance preparations of the Patriots, started measures against the hidden resources of the insurgents. The minutemen in the countryside had to be warned. On April 19th, Paul Revere, a local artisan who sometimes doubled as a courier, and two others rode to Lexington and Concord to warn the colonists. Although three men rode out at night, the fame rests on Revere. The reason was poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. In 1860 he composed a poem which became so well known that every school child in the US knows the ride of Paul Revere, but nobody has ever heard of Prescott and Dawes.

Paul Revere’s house on North Square in Boston was beautifully restored and is now a museum. Although they state that 90% of the house is in original state and even the wallpaper was original from the time when Revere owned the house, it is doubtful that anything of the wooden house really rests from the original construction of the 1600’s. Paul Revere has sold the house in 1800 and along with the entire neighborhood it fell into disrepair.

Paul Revere’s former neighborhood of North end is the oldest in Boston. It still preserves some buildings from the 18th century. After the revolution the area deteriorated into a seamen’s quarter full of bars and whores until eventually Italian immigrants took over. Today it is full of fancy restaurants and cafes in beautiful buildings.

The center of the neighborhood is old North church. Built in 1723 it is Boston’s oldest church building and has Boston’s tallest steeple. While Revere did his ride, a guy called Robert Newman climbed up the steeple and gave light signals. This was dangerous since it could have been seen by the British as well. However, Newman managed to get back into his bed undetected.

The interior of the church is basically unchanged since the colonial time. The chandeliers were first used on Christmas eve 1724 and still use candles. The clock and the organ were the first built in America and are still in use. Three statues decorating the organ were taken from a French ship by privateers.

Traditionally, in the 18th century the pews were sold to wealthy believers. Hot stones could be used to keep the believers warm during the long services. An audiotour explains who owned the pews. Poor and black people had to spend the service upstairs on the balcony.

One of the pews in the back was occupied by the warden. The warden had a long stick. If somebody misbehaved, was not quiet enough or fell asleep he used it to reprimand the culprit.

One pew was reserved for the British general Thomas Gage. This was an Anglikan church. Only about 1/3 of the colonists were Patriots. 1/3 were Royalists and 1/3 did what had the biggest advantage for themselves. So there always were people who wanted to share the church with the British general.

Boston quickly started to outgrow its colonial boundaries. Pre-revolutionary Boston basically was an island between Charles river and Mystic river. Incrementally the marshland around the island was drained to gain land. Faneuil’s hall wasn’t sufficient for the market any more and two big new market halls, South and North Market were added on new land behind.

A little bit of old Boston is preserved in the area close to the market halls. There are a couple of pubs which fit well into a port city. The Union Oyster house of 1826 is the oldest continuously operated restaurant in America. The green dragon originally was the headquarters of the revolution. The original building was torn down and replaced by a parking structure but there is a modern replacement.

Hay is not sold any more on the Haymarket. However, some of the free space is even in winter not used as a car park but on Fridays and Saturdays for an open air fruit and vegetable market.

.

Cobbs hill burial ground with Charlestown in the background

Across the Charles river is the Boston neighborhood of Charlestown. On June 17th, 1775 the British attacked the Patriots who had fortified the top of Bunker hill, the highest point in Charlestown. It was the first battle of the war of independence. The British won the battle. However, British casualties were high. Eventually they were not able to stay in town. On March 17th 1776 the British troops abandoned Boston. It took another 5 years until the British army finally surrendered in Yorktown in 1781. In 1783 the peace treaty was signed. The United States had become independent.

After independence Charlestown became one of the most important US Navy yards along the Atlantic coast. During world war II up to 50000 workers built, equipped and repaired the US Navy Atlantic fleet here. After 174 years the yard was closed under president Nixon in 1974. The reason might have been that Massachusetts had been the only state who had voted against Nixon in 1972. Revenge against the political opponents has a tradition among Republicans.

The area of the yard was redeveloped into housing. Part of the yard is the Charlestown Navy Yard National Park. Its most prominent exhibit is USS Constitution, one of the US Navy’s first ships built in a shipyard in Boston in 1797. The Constitution got the nickname “Old Ironsides” after she had shot several British ships to wrecks.

USS Cassin Young

The museum also houses USS Cassin Young, a destroyer built during the second world war. 14 similar ships were built in Charlestown during WW II.

The yard also preserves a dry dock. USS constitution had been the first ship to enter it in 1833 and the last in 1974.

It is quite a walk from my hotel in a former warehouse area on the other side of Boston across the Mystic river to Charlestown. Fortunately a regular ferry connects the Charlestown Navy yard with the former docks in Downtown Boston. The old docks are all rebuilt into housing estates. The lifelines of a busy harbor has disappeared. There is nobody around.

South End/Down town is the financial district of Boston. The number of big bank buildings is astounding. The few historic buildings are dwarfed by modern highrises. Like in many American town centers there are quite a number of historic business buildings with art-deco entrance-ways and rich ornaments meant to impress customers and passers-by.

Beacon Hill is probably the nicest neighborhood of Boston. Many of the buildings here were already built in the time before the Revolution. The houses are testimonies for the prosperity of Boston in the 18th century. The oldest standing structure is the George Middleton house of 1786. Middleton led a black militia company called the Bucks of America. He also organized an African society and was the Grand Master of the African Lodge.

At the time quite a number of African Americans were living in Beacon Hill. The national park service, who takes care of the monuments in Boston, offers a guided tour of Afroamerican history in Beacon Hill. Although there was no slavery in the northern States like Massachusetts the black inhabitants of Boston had to cope with racism and social and economic disadvantages. Institutions like schools were segregated. After protests the Phillips school in Beacon hill was the first school in Boston which admitted black students in 1855.

Like the schools the churches were segregated. After a member was expelled for bringing Afroamerican friends into his pew the Charles Street meeting house was bought by the First African Methodist Episcopal congregation in 1876. The congregation stayed in the church until 1939. It was the last African American organization to leave Beacon Hill. It later became a safe space for members of the gay, lesbian, and bisexual community.

Beacon hill also played an important role in the Underground railroad before the civil war. Safe houses like the Lewis and Harriet Hayden House provided shelter for slaves who had escaped from the South but had to hide from Slave hunters. Lewis and Harriet Hayden had escaped slavery in Kentucky themselves and set up a boarding house here.

After the revolution was a fact, the old state house was not sufficient any more. It was replaced by a new, big and representative building on Beacon Hill in 1798.

My first visit in Boston mid December saw nice warm weather and sunshine. When I come back a week later the weather had changed. The temperature has dropped to below zero and there had been snow. Although there was no problem with the trains on the line north of Boston the weather might affect traffic between Boston and New York. And indeed, when I arrive at South station the central hall is full of waiting passengers. All the Acela trains are canceled, some of the Northeastern are more than an hour late.

Besides the waiting passengers the hall is used as a shelter by the homeless. A giant stops next to me, looks at me and says something incomprehensible. When I do not reply he stays staring at me without saying another word. Eventually he continues to somebody else.

There are no gates or guards at Boston South station but there are free toilets. The toilets are a mess and in the back corner something unpleasant is going on.

The opening of Boston’s South station “will raise to a distinct higher level the expectation which Boston will hereafter make upon the traveler who visits our city, to compare it with others; for he will here find one of the very finest examples of a great passenger terminal to be found anywhere in the world, and the impression will be created upon his mind from the moment of his arrival that it must be no mean city which receives the stranger in such ample and dignified surroundings” Mayor Josiah Quincy said upon the opening of South station in 1899.

The five story neoclassical revival-style station forms the northern terminus of the North-East corridor. Although you would think there is enough space in Boston for new, modern high-rise development they had to expressly select the air space above the station to built another sky-scraper. The windy vault between its support pillars is illuminated in a ghostly islamic green at night. It is still under construction, so the space directly below is fenced off.

Waiting area Boston South station

I am waiting for the Northeastern train # 67 to New York. According to the App of Amtrak it is on time. Of course, again, I am far too early at the station. A number of earlier trains are bound to leave for New York and so I walk to the ticket counters to see whether I can change my ticket. Train # 177 is supposed to leave 75 minutes earlier than my # 67. However, they tell me that I would have to pay another 95 $ to change the ticket. So I go back to my seat in the waiting area.

Northeastern regional in Boston South station

It is good that I did not change my ticket. While I wait for # 67, the delay of train # 177 increases steadily. When the # 67 finally appears on the display it is the only train tonight which supposedly is on time and the delay of # 177 is such that it will leave after the train I have booked.

Meanwhile most of the fellow travelers have moved away from the company of the homeless in the waiting area of the main concourse towards the station hall where the trains are made ready for departure. Expectantly people have lined up at the end of a platform where a train looking like one of the Northeastern Regionals is waiting. There is no announcement and nobody steps forward to ask the employee who blocks access to the platform which train this actually is. When I finally ask it turns out that it will not be # 67, but # 177.

After a short while another train backs into the station and the majority of the crowd moves to the other platform assuming that it is # 67. I get into a conversation with the funny chap in line ahead of me who seems to take these trains regularly. He tells me that it is not really a problem if you take another train than what you reserved, in particular when trains are late and when it is for a short distance. And then, of course, it is always good to sit in the car next to the bar to be the first to get a drink.

When yet another train is pushed to the platform next to us it turns out that we have again waited at the wrong platform. This time we can board and # 67 leaves the dark, snow covered outskirts of Boston with little delay. Despite the cancellation of a number of trains there is plenty of leftover space. I do not spend the ride in the car next to the bar but in the silent car at the head of the train. And it is really silent and dark there. I doze away the time to New York.

Comparing a ride on Amtrak with a European, in particular German or Dutch train, is highly favorable for Amtrak or the US travelers. During my more than 10.000 km of train rides in 4 weeks I did not see a single drunken or misbehaved passenger on board, a nuisance which is common on German trains where rowdy drunkards board with whole cases or even kegs of beer. People usually travel quietly and silence in the special “silent” car is strictly observed. The trains are in general clean and there is no vandalism. In contrast to Dutch trains the garbage is regularly cleaned away and does not accumulate for days. The toilets could set an example for European railway companies. There are plenty of toilets on the trains and they usually work. Moreover there are free toilets in every Amtrak station. There also is plenty of space for luggage and excess luggage or bicycles, skis or other oversized items can be checked for free and collected at the destination. All trains have a cafe-bar. Longer stops with the chance for smoking are announced well in advance. If a smoker puffs on the train or would block the door at departure he is mercilessly left behind.

Sources:

Todd DeFeo, The Northeast Corridor, Images of Rail series

The complete guide to Boston’s Freedom Trail, Charles Bahne, 4. ed, 2013

Link to previous post:

No comments:

Post a Comment